Preservation – Physical or Digital?

Written by Judith // August 31, 2014 // At the Museum, Newsletters // No comments

Letter from the Director

This month’s newsletter features an article on why DGM focuses on physical preservation, the story of a wonderful artifact, the first of a four-part series on the history of adventure games, and an adventure game themed trivia question. Have fun!

We were sorry to cancel our exhibits at Japan Expo and Convolution, but our priorities are changing here at DGM. We’ve always participated in a lot of events around the area, but now that we have a space of our own we are spending more of our volunteer hours working onsite. Our collection is growing at an almost alarming rate – alarming because we are rapidly over-filling our space. We’ll be introducing a monthly evening event inviting you to help out at the museum with everything from database entry to dusting, and we’ll have expanded signups for a workday one Saturday per month. Stay tuned for announcements!

We are also forming some new alliances, beginning with the Sunnyvale Historical Society. We helped them set up a playable Atari for their new “Low Tech to High Tech” exhibit and will be putting up a small exhibit at the reception, Sunday September 7th. Stop by, say hello, and and meet our neighbors.

And we have added two new board members to our crew – we’ll be introducing them in future newsletters. Right now, Dave is working on fundraising and policy. Carl has been bringing old Ataris back to life and we now have a fleet of ten or more playable consoles for events. At least, he was – until daughter Courtney, who has taken photos for us, said yes to a marriage proposal from Alan, our web developer. So now they’re in full wedding planning mode. This is the second wedding for DGM volunteers so far; we can’t beat OK Cupid, but it looks like love blossoms at DGM!

Judith Haemmerle, Executive Director

Physical or Digital?

Digital preservation is a very hot topic in the museum field these days. There’s a lot of grant money available, and many museums are working on a variety of different initiatives. Some of these efforts involve massive coordination among multiple institutions, and others are widely distributed affairs. The uncertainty in the field of digital preservation is part of why we are focusing our attentions elsewhere.

A good example of what considerations go into digital preservation is the recent sale of Twitch to Amazon. Twitch, the world’s largest game streaming service, was deleting all their old archives. DGM founder and Board member, Ben, joined a team attempting to archive a lot of the content and made sure the group included some historically interesting channels like those featuring commercial advertising. So, in theory, archive.org has a good chunk of the old Twitch content now.

But why didn’t Ben save these archives on DGM storage? Because archive.org is spending more on storage for this one project than the entire lifetime budget of the DGM so far. It’s not something we are set up to handle, but since it’s being done other places, we don’t need to do it. Our digital storage has bit streams of game code, copies of culturally significant games like Flappy Bird, movies of local game celebrities, and other locally important bits of game history. Although it’s growing as new digital content comes our way, it’s not our focus.

In contrast, our collection of physical artifacts is growing at a very rapid rate. We’ve recently acquired over 100 game posters and arcade marquees, over 100 Atari related t-shirts (many of them in-house and never commercially available), newsletters from Atari’s earliest days (“I have a 55 gallon aquarium for sale . . .”), memorabilia like a monogrammed varsity jacket and the menu from Atari’s 20th Anniversary celebration, dozens of games in their original packaging, and more. Each of these artifacts tell a story of the culture of game companies and gamers as much as the games themselves do. We have said all along that we are not primarily about keeping the games themselves playable; we are a museum preserving cultural history focusing on the art form called video games. And we save stories, too.

So if you come and visit, you won’t find a lot of games set up to play. What you will find is that you are standing in the midst of the fragile things that represent the people, the events, and the devotion of game coders, artists, composers, designers, marketers and players. We take care of them so that you and future generations can say “Oh! So that’s what happened!” and then move forward with that knowledge into whatever comes next in gaming. We can learn from the past to make an exciting future, but only if we care for our past.

We save more than games – we save culture.

Adventure Games, Part 1: Colossal Cave and Infocom

Colossal Cave Adventure (1975-76)

Colossal Cave Adventure (often called Colossal Cave or Adventure) was the first adventure game and inspired all the adventures that came after it.

Drawing on his experiences playing Dungeons and Dragons and spelunking in real caves, Willie Crowther decided to create a game based on exploring Mammoth Cave in Kentucky to entertain his daughters, whom he was missing after his divorce. It was written in Fortran on a PDP-10; there were about 700 lines each of code and data.

Infocom (1979-1986)

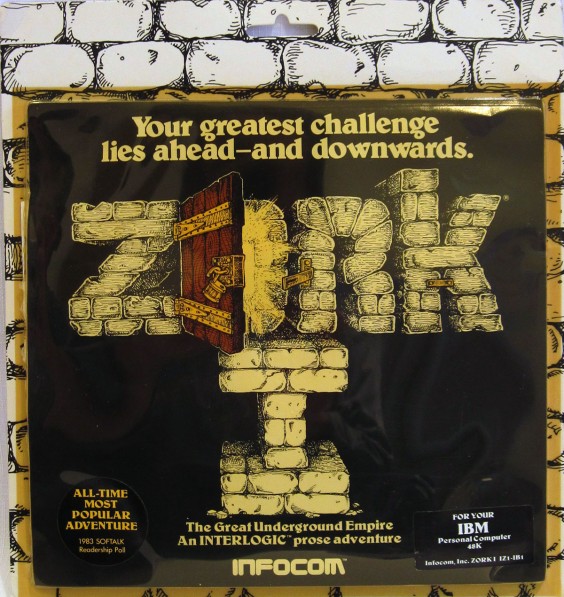

Colossal Cave Adventure swept through colleges across country via the ARPAnet (the precursor to the Internet). By May, 1977, the game had been solved at MIT by a group called the Dynamic Modeling Group who believed that they could improve upon Colossal Cave. Working on a PDP-10 in MUDDLE (MDL), Dave Lebling wrote a command parser; Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Tim Anderson worked on the design; and Blank and Anderson did the bulk of the coding. More sections of the map and puzzles were added over 1977-1979. The resulting game was called Zork.

Infocom was incorporated in 1979 by MIT staff and students, including Lebling and Blank. Intended to be a commercial venture, there was no fixed idea about what products would be developed. Selling Zork seemed like a good way to finance their future products, so Joel Berez and Marc Blanc developed a virtual machine called the Z-machine Interpreter (ZIP) and the Zork Implementation Language (ZIL) that allowed Zork to run on a personal computer. The scaled down Zork was released for the TRS-80 Model I in 1980.

Infocom dominated the adventure genre for many years. Noted for rich language, imaginative plots and engaging characters, Infocom boasted that it relied on the world’s best graphics processor – your brain. The graphics of the time were poor contenders. The demographics of computer owners (well educated and well-to-do) eliminated barriers to games that demanded a lot of reading. After an unsuccessful start with marketing by Personal Software, Inc., Infocom took over themselves, and they packaged the games with amusing extras that were sometimes essential to solving the game. Swamped by requests for help, they invented InvisiClues, booklets with invisible hints that were made visible by a special marker.

In 1982, work began on a relational database later named Cornerstone. A Business Division was formed, and the number of Infocom employees went from 32 to 100 to staff it. Game sales had slowed and the high-tech sector suffered a slowdown in 1985. Tensions developed between the game and business divisions, partly because the financial demands of Cornerstone left the game developers without resources to innovate. Instead of the growth increase that had been expected to fund Cornerstone, revenues were stagnant. Competition from graphical games also impacted Infocom sales. In September, 1985, layoffs began; by the end of 1985, there were 40 employees left.

Cornerstone faced stiff competition in dBase, and although the product got excellent reviews, it did not capture a significant market share. In l986, Infocom merged with Activision. In 1989, Activision laid off more than half of Infocom’s remaining employees and closed the Cambridge office. Only five of the remaining employees re-located. It was the end of Infocom and the Golden Age of the text adventure.

The “Loser Ribbon”

In December, 2009, LucasArts held its first “Dream Week”, an event in which employees were divided into 20 teams and given a week to craft the game they most wanted to make. At the end, 10 ribbons were awarded for categories such as Best Graphics, Best Sound, etc. The team that made Lucidity did not win any ribbons, but later LucasArts decided to put the game into production and the finished product stands as the only LucasArts game released that originated from a Dream Week . A member of the original Lucidity team then tracked down the manufacturer of the ribbons awarded to the other teams and had “loser” ribbons made for each of the team members. These ribbons say “Loser” where the real ones say “Winner,” and say “But our game got made” where the real ribbons state the category won. Lastly, each ribbon category had its own color ribbon, but these were made in black – a color unused for any of the real award ribbons.

Thanks to game designer and member of the original Lucidity team, Chip Sbrogna, for donating this great artifact and story to DGM.

Artifact number 2014.024.001. Lucidity is available on Steam and XBox Live Arcade. Photo by Brian.

This Month’s Trivia Questions

How many of the “Feelies” included in the Infocom gray-box edition of The HitchHiker’s Guide to the Galaxy can you name?

(Hint: There were 7, but no towel or Babel Fish, so it wasn’t very useful for space travel.)

Last Month’s Trivia Answers

What Infocom game started as a joke title filled in on the office release calendar?

Leather Goddess of Phobos